OCD Does NOT Improve Athletic Performance

How My Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Tried To Steal My Passion for Endurance Athletics

by Katie O’Dunne

Worries — that is what my family called the thoughts in my head. In elementary school, I worried that if I didn’t touch objects in a particular order or offer complete honesty, catastrophe would ensue. I confessed the tiniest moral imperfections, receiving reassurance that I was a good person. As I grew older, endurance athletics became an outlet for my untreated OCD. However, unlike articles you read where OCD leads to dedication that enriches athletic performance … my focus on the thoughts in my head severely diminished my potential and enjoyment of the sport I valued so deeply.

I spent my collegiate career as a Division I runner at Elon University, eventually becoming the cross country captain. I was seen as the “perfect student-athlete,” receiving awards for my 4.0 each semester while performing at a high level. And yet, I spent most of my time alone checking the oven, stove, and locks for hours on end to prevent a fire or an intruder. After completing this process, I would pray nothing catastrophic would happen, lay down in bed, and nervously repeat the process for hours. I was skilled at keeping my compulsions hidden to maintain the facade of perfection. I often wonder how much further I could have propelled my running performance if I was actually able to sleep rather than compulsing all night, or perhaps if I didn’t physically punish myself for every single calorie that entered my body. Thankfully, in college, running served as somewhat of a safe-haven for clearing my head. However, as I continued to travel further down the rabbit hole of OCD, the disorder crept into every aspect of athletics for me.

Following college, I began a masters degree in theology at Emory, pursued ordination, and began my work as a school chaplain. I was fearful that a diagnosis of OCD would end my career in ministry, so I remained untreated, seeking to use endurance athletics as an outlet for my pain. By this time, my thoughts began focusing on death and harm, as I believed that I was a dangerous individual despite my altruistic vocational path. To those watching me, I was just a happy chaplain diving head first into the sport of triathlon. And yet, I spent each night obsessing that I had called someone a derogatory name, shouted obscenities, touched someone inappropriately, kicked a child on crutches, or written something nasty on a birthday card before blocking it out. I spent my nights ruminating to prepare for a call from the police and my days carefully taking pictures of actions to check later. My long runs, bikes, and swims were no longer a place of solace. Rather, they gave me 20+ hours a week to attempt to “figure things out in my head” while mindlessly training.

Throughout my triathlon career, I competed in countless races with more podium finishes than I can remember. The highlights are two world championships, along with 10 Ironman races. And yet, when I recall these races, I don’t remember the finish time, the experience, or the podium position … I simply remember whatever I was obsessing about at that given time. I spent entire races completely checked out of my body, simply trying to figure out or pray away my obsessions.

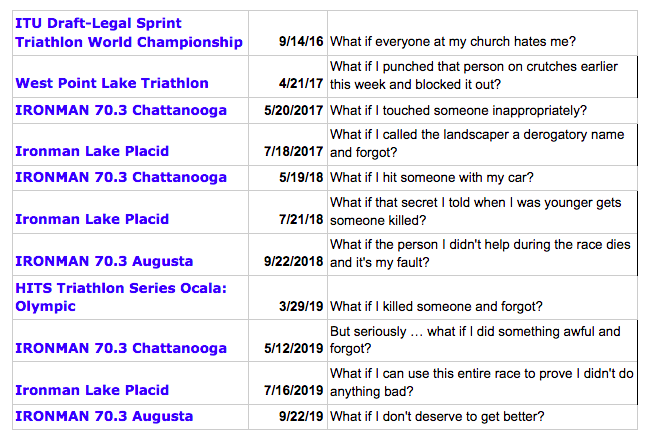

Here are just a few examples:

This chart represents 11 of close to 50 triathlon races over a five-year period of struggle. Each race consisted of hours of ruminating, trying desperately to prove I wasn’t a horrible person rather than being present in the race. In 2018, I even fractured my femur during Ironman Lake Placid, running over 20 miles on it. I cannot recall the pain but simply the fear that I had said something appropriate and offensive to someone the week before the race, that I was a horrible person, and that I would lose my job as a result.

I was lucky enough to find and move through evidence-based treatment. Support networks, ERP, ACT, and medication saved my life, allowing me to begin to love myself once again. While OCD treatment can seem challenging, I learned that nothing in life is certain. Rather, the only thing that’s certain is that I would continue to give up every ounce of the life I cared about if I continued to indulge my OCD. I chose to take the leap by choosing the things I value most in my life over the certainty I desperately sought for so long. One of my biggest values is endurance athletics. I am now training and competing as an ultra-runner, with a focus on being present and enjoying the journey for the first time in my athletic career. While OCD does not help you become a stronger athlete, choosing a value that is important to you (like athletics!) can help you choose this value over the certainty you desperately desire.